Victoria in space

connection is impossible.

There was a point in my life

where I lived in a place that felt

like a shoebox and

I never thought

I would live

somewhere smaller.

It turned out I can live somewhere smaller

—I signed up

to man this shuttle

and float in space for a year.

The irony of feeling like

I don’t have enough

space

in

space

isn’t lost on me. Trust me.

It also isn’t lost on me

that I am more disconnected

than I have

ever been

in my entire life.

That isn’t and shouldn’t be a surprise.

Tiny space,

alone,

so far away I might as well be dead.

Disconnection.

Makes sense.

Where could I find

connection

up here anyway?

How could I find connection

in the stars,

a million million miles away

from even someone I can’t stand,

let alone

someone I love?

I have more in common with

roiling balls of gas,

chunks of rock, hunks of ice,

clouds of comets,

a meteor with a tail a thousand miles long.

There’s romance there,

at least on paper.

There’s romance in the thought of celestial connection,

just like there is with oceans and earth and mountains

and flames.

I miss the connection I had in my tiny apartment

with my partner and my dog,

with my friends and my community,

but I still wonder:

maybe I signed up for this time in space

long before

I got there physically;

maybe I have always dreamed of one thing

while pretending I want another;

an alien actor in an alien body with an alien mind and an alien heart.

It’s such a

funny thing

to yearn for the

deepest sort of connection, even knowing that

connection is impossible.

Up here,

where there is no day or night,

only awake and asleep,

where there are no seasons,

only pages flipping on a calendar.

It’s only me up here,

me and all the things

I can say I want,

tell myself I want,

that I can pretend to want.

All I have to do is watch

the universe

pass by,

push buttons and keep logs,

and dream about everything

that awaits my return

and I hope

I want what I tell myself I want.

Return home

The shadows are always a good reason to be with someone.

It’s hard to imagine

life

on the station ever coming

to an end,

that a day will come when I

can return to Earth and be around other people.

I stopped counting the days I’ve spent up here

because

day and

night

don’t really exist. Maybe

they never

existed on Earth either, and

it’s always been just a way to

try and stay together.

The sunshine is always a good reason to be with someone.

The shadows are always a good reason to be with someone.

Up here,

the sunshine and shadows exist,

but they aren’t the same thing as down there.

When you can lower the sunshield and

stare at the sun for hours and hours, sleep under its rays,

it isn’t really the same as knowing when

it will rise and

when it will set.

Just the same, every waking moment

can be spent in shadows up here.

I wonder what it will be like

when I finally land,

soil under my feet,

real moisture in the air,

with real sunlight touching my skin,

real moonlight touching my skin.

What will the phases of the moon feel like?

Will the glitter of the stars still mystify me?

I hope so.

I hope the return is just as exciting as the exit was.

I hope finding a way to reconnect after so long in space

is as refreshing as I found disconnecting to be.

I hope there is less pain than there was before,

less fear,

less anxiety,

less depression,

and I hope there is less

desire to disconnect

and flee to the void

under some pretence

of being a watcher in the sky.

I know my time up here,

floating all by my lonesome

will come to an end

and it is hard to imagine the return.

Hull breach

Of course, couldn’t and wouldn't were only truth

until the truth changed.

I used to dream

about living

on a space station but

I always knew

it could never happen,

it would never happen.

Of course, couldn’t and wouldn't were only truth

until the truth changed.

Still, I thought

everyone

I imagined

who lived up on the space stations

would be scientists

and geniuses

and doctors

and engineers

and researchers

—people who really had something going for themselves,

and who wanted to build a better world.

I never thought there would be anyone like me up here.

As a kid,

I read science fiction,

I watched the movies

and the shows

and played the games

and read the comics,

so a part of me knew

a normal person could end up in space somehow,

but I ignored

how often it was a mistake

or a punishment

or a suicide mission.

I just didn’t think normal jobs existed up there

past the clouds.

I thought life

would somehow be different

than down in the fires.

I never thought

I would be flipping burgers in Saturn’s orbit,

but here I am.

Here I am

doing something I never thought possible

and it’s the most

painful

thing I’ve ever done.

I am praying for a hull breach.

Asteroid impact

I, however, want to know I haven’t left money on the table

Watching that asteroid hanging in the sky every day

taught me how precious each moment could be,

but it wasn’t always that way.

Seeing a mass

one hundred kilometres wide

bearing down all day.

all night

does little to inspire hope.

Knowing it would only be a year until

the New Moon crashes down

left a vacuum,

a world devoid of

love, hope, compassion, touch, scent, sound, vibration, energy, and faith,

where there are no more spectrums

and no more starts or finishes.

One is left with only now.

Only a collection of ugly, unshaped moments

to be carved and whittled and molded into renewed brilliance

glittering defiantly in the face of extinction.

Of course, the New Moon will come down

and all of this will come to bear as just

a path to death and transformation

and letting go of comfort is never easy.

There are still people staring up,

thinking and maybe believing

we can steer the New Moon away from Earth.

Maybe we can even mine it.

Maybe we can strike a bargain with god while we’re at it.

Only a man can think of escaping by a nut hair

and have the gall to make a demand.

But,

I understand the Great Fear.

I understand looking up at the asteroid

and knowing how much time is left,

how every minute past is a minute lost

and every minute lost is one where a sense goes unused.

Some sound unheard,

some sight unseen,

some flower unsmelled,

some fruit untasted,

some beauty untouched,

some emotion unfelt.

Of course,

sometimes

feeling nothing,

ignoring everything

on an abstract timeline is what allows for existence;

in a world with an ageless earth and an indeterminate lifespan

everything can be deferred.

Hearts can go unbroken,

promises can be be kept,

hopes never failed,

and

dreams never killed.

I, however, want to know I haven’t left money on the table

when the New Moon,

a hundred kilometres wide,

blasts through the atmosphere.

Whatever my life turns out to be,

I want my senses burned out and emptied.

I don't want anything left unfelt.

I want to

stand and feel

the heat and

the shockwave and

the final rush

before I become dust.

Stepping in shit

I miss making a stupid joke to get a cheap laugh.

Everyone always says when you get to space

you will miss your friends

and you will miss your family

and you will miss your partner

and you will miss getting drunk

and you will miss having sex

and you will miss someone smiling at you

and you will miss a warm breeze

—a real warm breeze,

not what the shuttle processes and fires back—

and you’ll miss a real homecooked meal

and you’ll miss a dog barking

and people laughing

and being too hot and being too cold.

I was even told I would miss things like

sleeping through an alarm clock,

a nightmare in a real bed,

running out of hot water in a real shower,

stepping in dog shit,

getting a fucked up takeout order,

dropping the last bottle of beer,

driving over a nail.

Another person told me I would miss

finding out a cheque didn’t clear,

seeing my bank account in the red,

getting dumped and have never seen it coming,

even getting in a car accident.

Someone told me I would miss hating someone

more than I missed loving someone.

Someone else told me they missed the blowout

that caused the make-up sex

more than they missed the make-up sex.

And another person told me they missed the monotony

of the monotony.

One person

missed the neutral

and the boring

and all the things that don’t matter,

that never mattered,

that will never matter

and there are some things that just don’t matter.

After I thought about it all

—because what else is there to do

stuck up here

on your own

in this floating piece of scrap

for three years—

I started to wonder,

if I am alone

so far away from another person that

I am as far removed as removed can be,

do I even exist?

I haven’t been able to shake that question since.

No one warned me about this happening

when I signed up for this.

Everyone warned me about the little things

—sex and love and dogshit—

without telling about the Biggest Thing:

I am so far away

in every sense

that I am an abstraction.

I am an idea in the back of the mind.

It doesn’t matter

if my ship is hit by an asteroid.

Three days will pass before anyone even knows,

and that reminded me of life

before the technology that could put me where I am.

Things took time and maybe

the mailed letter arrived

and maybe it didn’t.

Sometimes the medicine is what did you in.

Funny that being in space,

locked in a shuttle,

this is where the world shrinks.

Out here,

alone in the void,

this is where my world is as small as it will ever be,

this is where I am living death,

this is where I am existing between worlds,

between realities,

between existence and non-existence.

And everything everyone told me is true,

even when they didn’t mention the same thing.

I miss laughing at stupid jokes.

I miss getting drunk on a Friday.

I miss not paying for parking and not getting a ticket.

I miss tipping someone more than I can afford.

I miss making a stupid joke to get a cheap laugh.

I miss complaining about the banal and the boring

and I even miss stepping in dog shit.

Stepping in your own shit just isn’t the same.

Do you believe?

no matter how I want the world to be,

it will almost always be another way.

When I first got to my station

it was to swap out with someone who had been up here

for almost three years.

I thought he looked pretty good for someone

who’d been alone for that entire time.

I’d been warned that so much time on your own can be

bad for your health,

but it didn’t seem like that was the case.

I saw a person who’d maintained their fitness regimen,

had been eating as well as one could up here,

had been keeping up proper hygiene practices

and seemed like they’d followed all of the steps

they were told would help get them through

all that time alone.

When the shuttle dropped me off,

the only thing

I was asked by the person I was replacing

was if I still believed in god.

I half-laughed and asked why

and I was told

being in space changes the way a person sees the universe.

Maybe there isn’t a god who made everything

and if anyone down on the earth thought they were

special

maybe they’d never seen an asteroid shower up close

or watched a solar flare or floated through space dust;

or maybe the idea that a god,

any god,

if they could make life on one planet,

and they had created the entire universe,

why would they have just stopped at one planet?

I didn’t have an answer for that one,

because I was still trying to get my head around the question:

do I still believe in god?

I don’t know.

It made me wonder if I ever had.

It made me wonder what I even thought about the whole thing.

I understand how one could try and find solace

in a cold world,

believing in being special and chosen,

unique amongst the earth and the firmament,

but the line of thinking loses steam

once one leaves earth for the time time.

Maybe that’s what my forebearer was trying to tell me:

no matter what I think I know, I never know a thing.

Whatever god I believe in, something will change it.

No matter how I understand the world to be,

it is almost always another way;

no matter how I want the world to be,

it will almost always be another way.

No matter how I think being alone in space for three years will be,

it won’t be that way.

It will always be another way,

and there will always be something that will

force us out of our doldrums.

Do I still believe in god?

Thirty-five months later up here in space,

I’m getting ready to ask the next person the same question:

do you still believe in god?

Synthetic everything

But we know how it always is:

nothing is real

nothing is true

until it’s happening to you.

Up here,

everything is fake.

Everything is synthesized,

out of a bag,

3D printed,

made out of whatever it is that sort of thing

is even made out of.

When I got sent up to space,

it wasn’t because I was the smartest

or the strongest or the fastest or bravest

or the best at anything.

Being plucked out of a crowd

meant

I wasn’t even the luckiest.

When I was a kid, my father told me

don’t come first

don’t come last

don’t volunteer.

I’m sure he would add don’t get drafted to that list.

But what are you gonna do?

Can’t have a real military without soldiers,

and anyone can be a soldier if they’re called a soldier.

That’s just how things are

now that it’s about spaceships

and about lasers

and rockets

and aliens

and existential panic.

Everyone—whatever that means—says it’s never been like this before,

but I remember

it was like this when the plague came.

I bet it was like this when settlers invaded, too,

driving away

and enslaving

and murdering

people who’d called the land home before time was time.

That was always different, everyone said.

But we know how it always is:

nothing is real

nothing is true

until it’s happening to you.

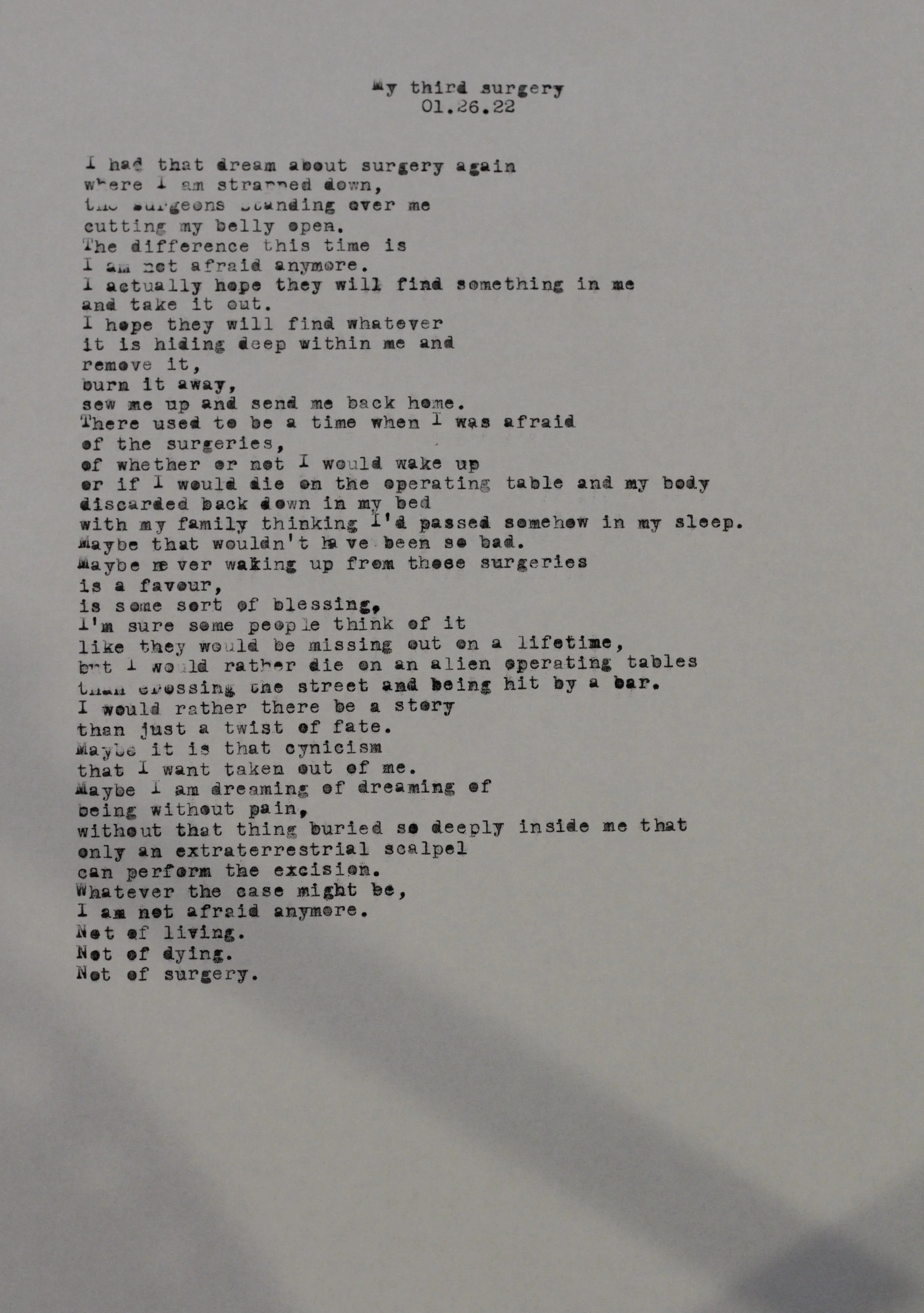

My third surgery

The difference this time is

I am not afraid anymore.

I had that dream about surgery again

where I am strapped down,

the surgeons standing over me

cutting my belly open.

The difference this time is

I am not afraid anymore.

I actually hope they will find something in me

and take it out.

I hope they will find whatever

it is hiding deep within me and

remove it,

burn it away,

sew me up and send me back home.

There used to be a time when I was afraid

of the surgeries,

of whether or not I would wake up

or if I would die on the operating table and my body

discarded back down in my bed

with my family thinking I’d passed somehow in my sleep.

Maybe that wouldn’t have been so bad.

Maybe never waking up from those surgeries

is a favour,

is some sort of blessing.

I’m sure some people think of it

like they would be missing out on a lifetime,

but I would rather die on an alien operating table

than crossing the street and being hit by a car.

I would rather there be a story

than just a twist of fate.

Maybe it is that cynicism

that I want taken out of me.

Maybe I am dreaming of dreaming of

being without pain,

without that thing buried so deeply inside me that

only an extraterrestrial scalpel

can perform the excision.

Whatever the case might be.

I am not afraid anymore,

not of living,

not of dying,

not of surgery.

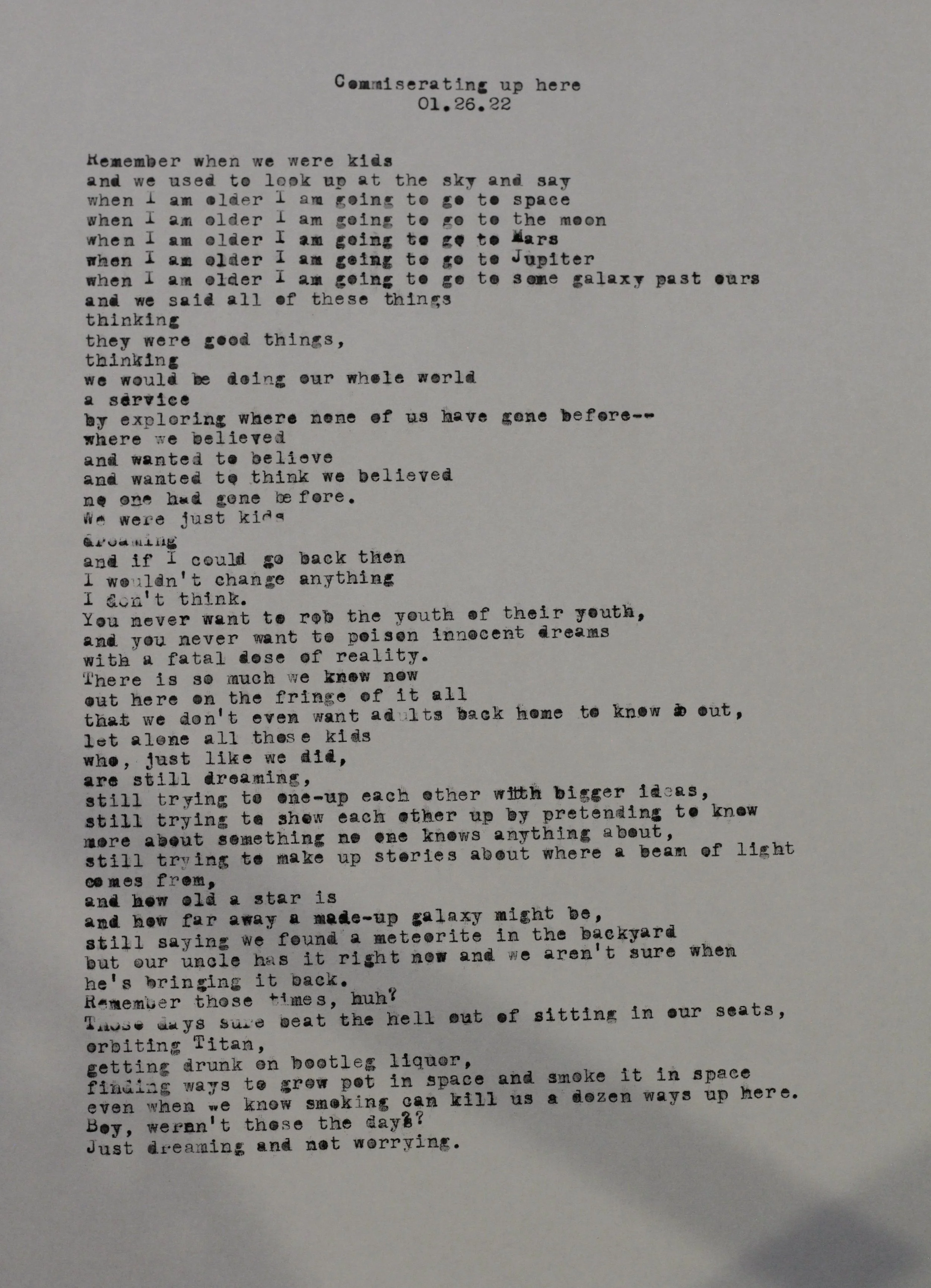

Commiserating up here

We were just kids

dreaming

Remember when we were kids

and we used to look up at the sky and say

when I am older I am going to go to space

when I am older I am going to go to the moon

when I am older I am going to go to Mars

when I am older I am going to go to Jupiter

when I am older I am going to go to some galaxy past ours

and we said all of these things

thinking

they were good things,

thinking

we would be doing our whole world

a service

by exploring where none of us have gone before—

where we believed

and wanted to believe

and wanted to think we believed

no one had gone before.

We were just kids

dreaming

and if I could go back then

I wouldn’t change anything

I don’t think.

You never want to rob the youth of their youth,

and you never want to poison innocent dreams

with a fatal dose reality.

There is so much we know now

out here on the fringe of it all

that we don’t even want adults back home to know about,

let alone all those kids

who, just like we did,

are still dreaming,

still trying to one-up each other with bigger ideas,

still trying to show each other up by pretending to know

more about something no one knows anything about,

still trying to make up stories about where a beam of light comes from

and how old a star is

and how far away a made-up galaxy might be,

still saying we found a meteorite in the backyard

but our uncle has it right now and we aren’t sure when

he’s bringing it back.

Remember those times, huh?

Those days sure beat the hell out of sitting in our seats,

orbiting Titan,

getting drunk on bootleg liquor,

finding ways to grow pot in space and smoke it in space

even when we know smoking can kill us a dozen ways up here.

Boy, weren’t those the days?

Just dreaming and not worrying.

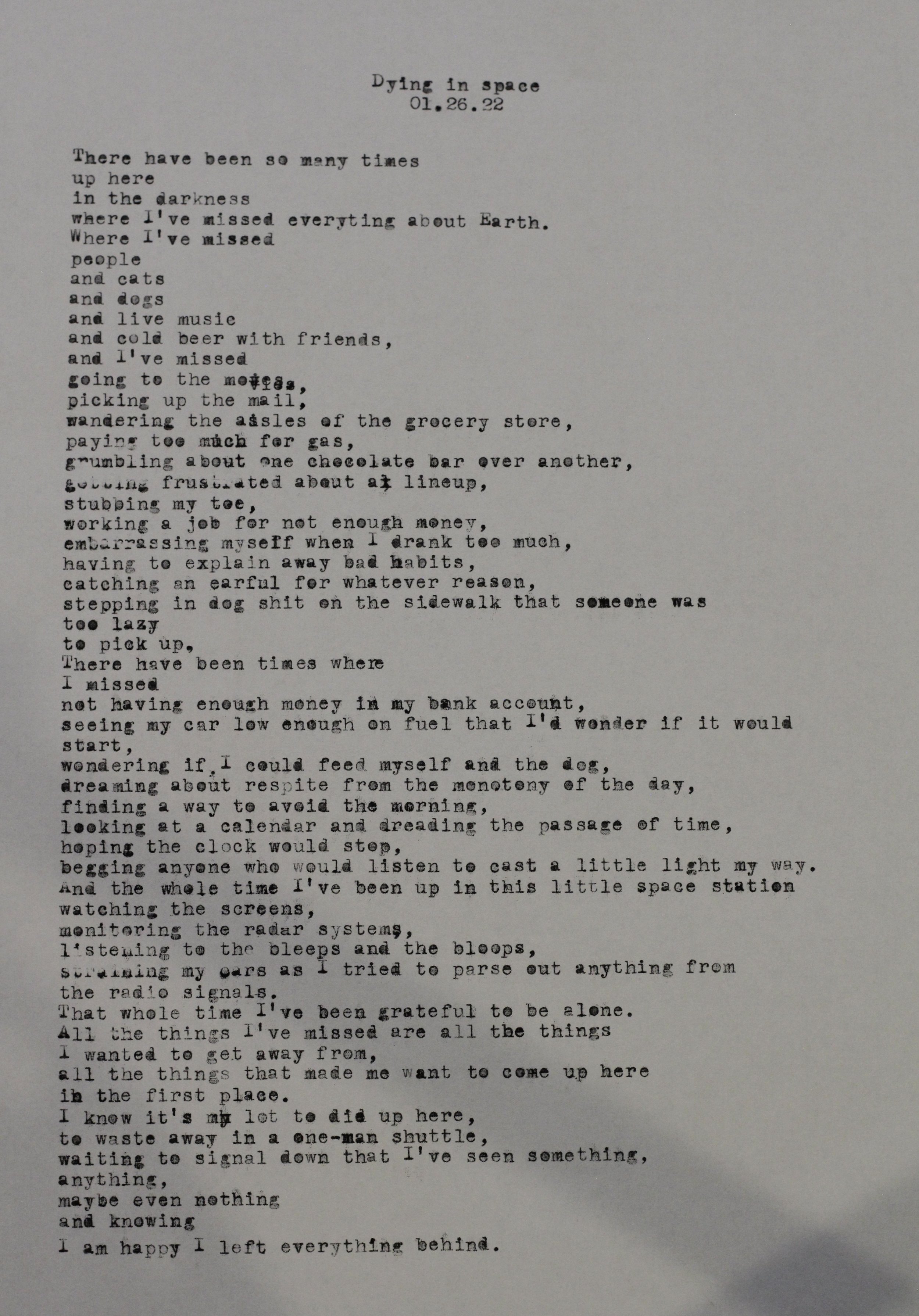

Dying in space

I am happy I left everything behind.

There have been so many times

up here

in the darkness

where I’ve missed everything about Earth.

Where I’ve missed

people

and cats

and dogs

and live music

and a cold beer with friends,

and I’ve missed

going to the movies,

picking up the mail,

wandering the aisles of the grocery store,

paying too much for gas,

grumbling about one chocolate bar over another,

getting frustrated about a lineup,

stubbing my toe,

working a job for not enough money,

embarrassing myself when I drank too much,

having to explain away bad habits,

catching an earful for whatever reason,

stepping in dog shit on the sidewalk that someone was too lazy to pick up.

There have been times where

I missed

not having enough money in my bank account,

seeing my car low enough on fuel that I’d wonder if it would start,

wondering if I could feed the dog and myself,

dreaming about respite from the monotony of the day,

finding a way to avoid the morning,

looking at a calendar and dreading the passage of time,

hoping the clock would stop,

begging anyone who would listen to cast a little light my way.

And the whole time I’ve been up in this little space station

watching the screens,

monitoring the radar systems,

listening to the bleeps and the bloops,

straining my ears as I tried to parse out anything from

the radio signals.

That whole time I’ve been grateful to be alone.

All the things I’ve missed are all the things

I wanted to get away from,

all the things that made me want to come up here

in the first place.

I know it’s my lot to die up here,

to waste away in a one-man shuttle,

waiting to signal down that I’ve seen something,

anything,

maybe even nothing

and knowing that

I am happy I left everything behind.

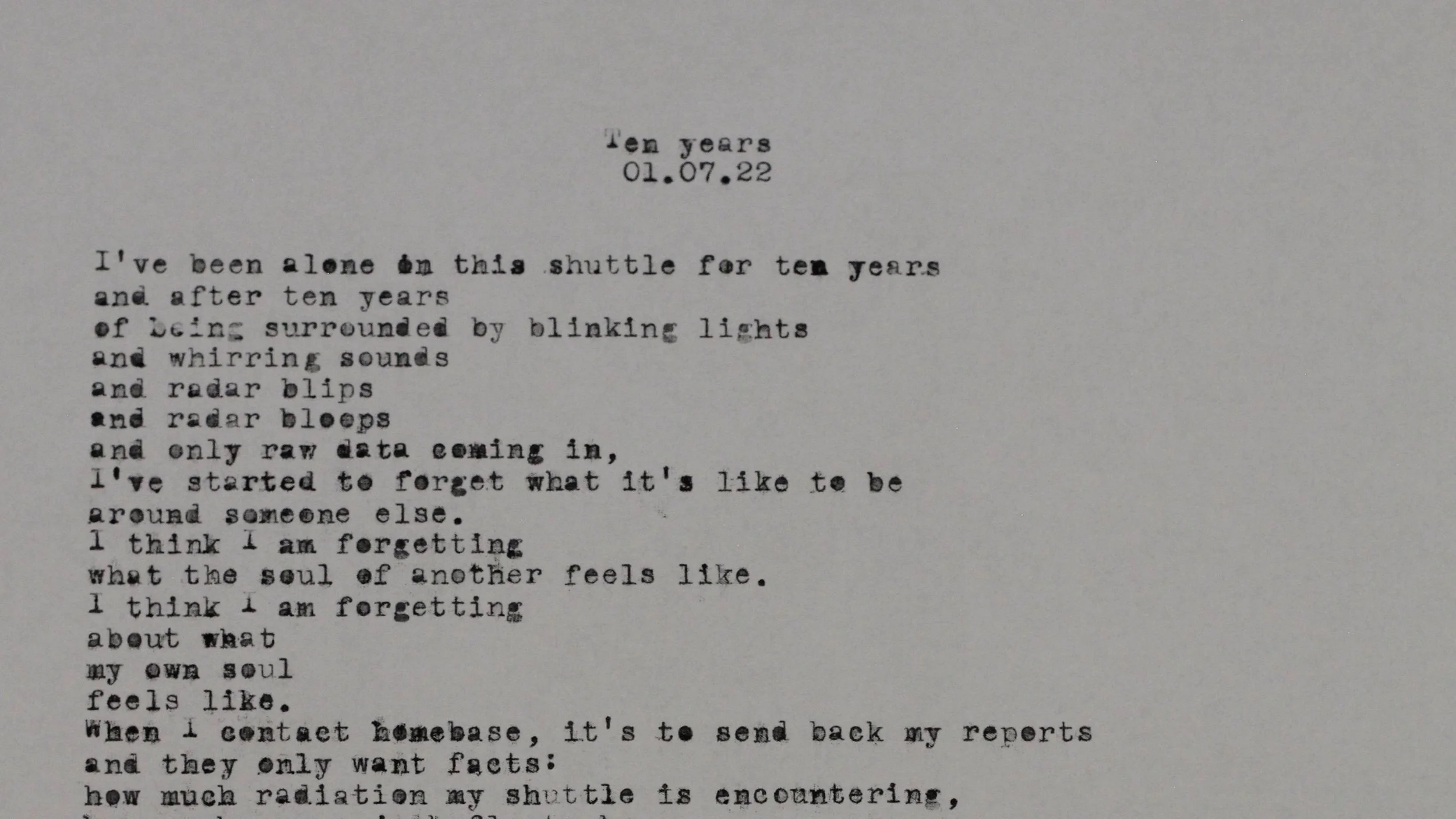

Ten years

I can’t tell them about isolation or fear or longing.

I’ve been alone on this shuttle for ten years

and after ten years

of being surrounded by blinking lights

and whirring sounds

and radar blips

and radar bloops

and only raw data coming in,

I’ve started to forget what it’s like to be

around someone else.

I think I am forgetting

what the soul of another feels like.

I think I am forgetting

about what

my own soul

feels like.

When I contact homebase, it’s to send back my reports

and they only want facts:

how much radiation my shuttle is encountering,

how much space junk floats by,

are there any radio signals

or subspace signals.

Things like that.

I don’t get to tell anyone what I think

any of it means.

I can’t tell them about isolation or fear or longing.

That isn’t my job out here.

My job is to collect, not interpret.

Never to interpret,

nevermind if whatever gets back home is old news anyway.

They told me they only want unfiltered data

so they can approach it from a fresh viewpoint.

I understand that to a degree,

but

what I understand more is the unfiltered data lets homebase decide

what any of it means before anybody else can have a say.

I remember during the plague when

nobody knew what was going on.

Nobody knew

who was calling the shots,

nobody knew

when things really went south

what might happen.

Too many cooks in the kitchen, in a way.

But,

in another way,

too many politicians in a room.

Too many people who only cared about themselves in a room,

too many people who wanted to pretend to pretend

they cared about others in a room.

Being out here, it doesn’t feel altogether different.

Being out here in deep space,

it feels like nothing matters.

Being alone for this long,

with just the bleeps and bloops to keep me company

I wonder why I even keep sending anything back

anyway.

I don’t know if any of it even matters.

I haven’t listened to music in ten years.

It was early on when I had a power issue

and my music archive corrupted.

Whatever I think a song sounds like

isn’t what it sounds like,

isn’t what it sounded like,

but,

instead

it sounds like whatever I imagine it sounds like.

Can you imagine thinking

James Brown sounds different than how he sounded?

It’s been so long I might not even remember

the sound of his voice.

That’s what I worry about out here,

that I forget everything.

Maybe that’s why homebase doesn’t want me

interpreting anything.

Maybe they know being in space alone for this long

does something

to the mind.

Maybe they are worried I will corrupt the data

unintentionally,

even intentionally.

Maybe they know that a man who forgets what the heart of

another man,

another woman, or

another person feels like

loses track of what being a human feels like.

Maybe homebase is worried the distance of

time and space

is too great

for anyone to survive.

Maybe they are right.

Maybe they guessed right.

If they had an idea about being right though,

why did they let me come on this mission?

Why would they even let me leave in the first place?

I can’t even remember what the O’Jays sound like anymore.

I’ve been alone on this shuttle for ten years

and I just want to go home.

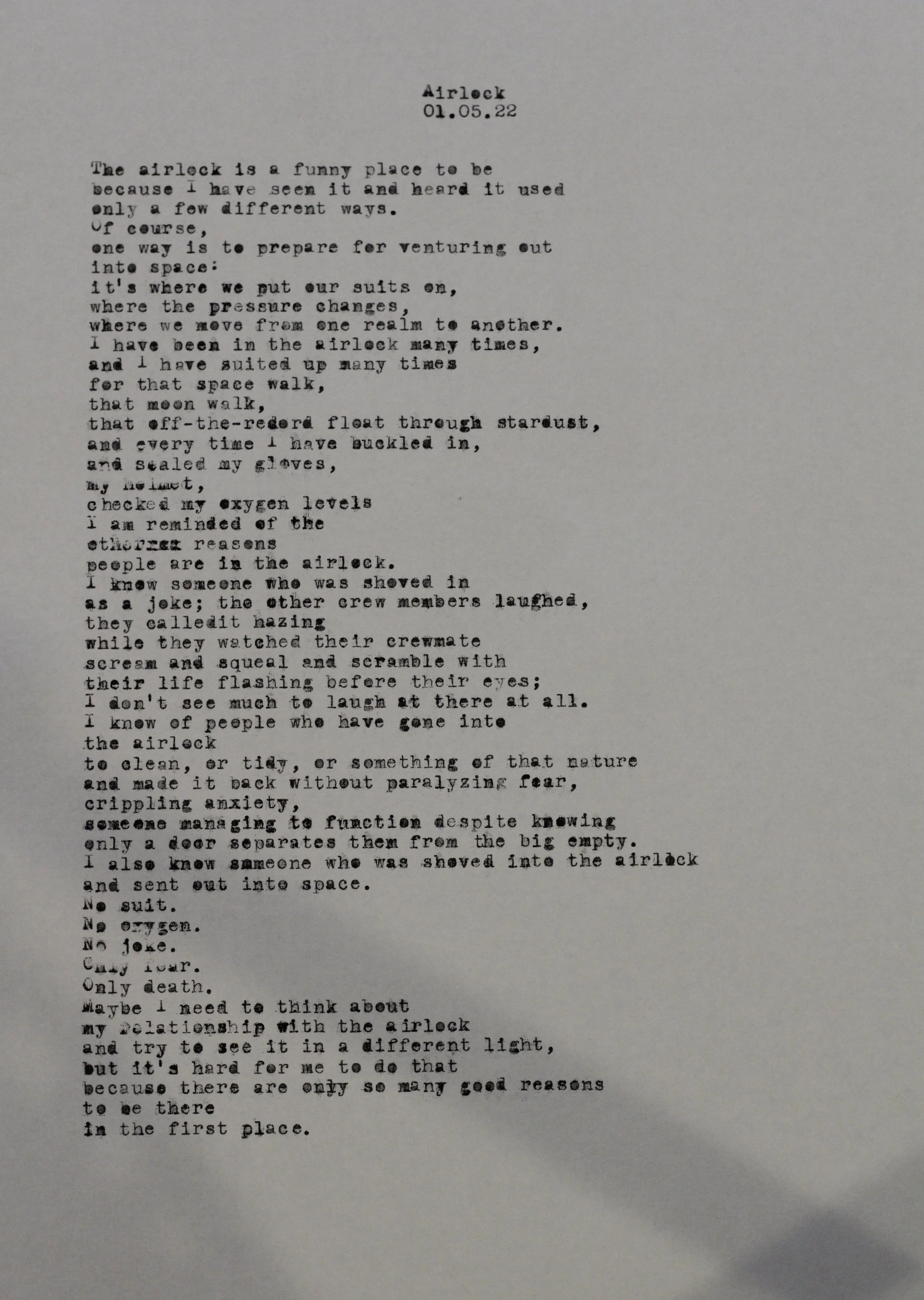

Airlock

I don't see much to laugh at there at all.

The airlock is a funny place to be

because I have seen it and heard it used

only a few different ways.

Of course,

one way is to prepare for venturing out

into space:

it’s where we put our suits on,

where the pressure changes,

where we move from one realm to another.

I have been in the airlock many times,

and I have suited up many times

for that space walk,

that moon walk,

the off-the-record float through stardust,

and every time I have buckled in,

and sealed my gloves,

my helmet,

checked my oxygen levels

I am reminded of the

other reasons

people are in the airlock.

I know someone who was shoved in

as a joke; the other crew members laughed,

they called it hazing

while they watched their crewmate

scream and squeal and scramble with

their life flashing before their eyes;

I don't see much to laugh at there at all.

I know of people who have gone into

the airlock

to clean, or tidy, or something of that nature

and made it back out without paralyzing fear,

crippling anxiety,

someone managing to function despite knowing

only a door separates them from the big empty.

I also know someone who was shoved into the airlock

and sent out into space.

No suit.

No oxygen.

No joke.

Only fear.

Only death.

Maybe I need to think

about my relationship with the airlock

and try to see it in a different light,

but it’s hard for me to do that

because there are only so many real good reasons

to be there

in the first place.

Little green men

They were not happy.

No one knew what to do when the ship crashed

and the crew,

all little green men,

came running out

shrieking and squealing,

looking like drunk children as they howled at the sky,

desperately trying to communicate,

begging for help,

for someone to do anything to save them

from burning to death.

But that isn’t the way here.

I remember watching on the news as armies moved in.

Instead of offering help,

the little green men were taken away.

Those who survived, they weren’t helped for their benefit.

They were locked up,

tested

experimented upon

like they weren’t real,

like they didn’t hold a shred of essence or soul,

just some new test subjects

to poke and prod.

World governments felt so

righteous

and full of themselves,

claiming they’d held back an alien invasion,

which wasn’t what anyone saw.

What everyone saw were frightened beings

running from a burning ship,

terrified of what they saw,

begging for things to be another way,

begging for their world to be how it used to be,

begging for reality to be anything but reality.

All those proud men and women in their suits

and in their uniforms

with their pitch perfect voices,

their polished words,

their messages coming across as

just-so;

they all stood at pulpits and altars

raving about their own virtues,

and so busy fawning and gawking over themselves

they didn’t notice when the second ship landed.

And it was not full of little green men looking for help.

It was full of those who’d seen

their friends, relatives, colleagues, and lovers locked up,

electrocuted,

burned,

poisoned,

tormented,

deprived of sleep and food,

all used in the name of science.

They were not happy.

They were full of fire and fury,

and human hubris was never more on display

than in the look of surprise on the faces of

all those stuffed shirts.

Where so many had wailed and moaned about the

resilience of humankind,

the never-lay-down attitude and the virtues of

seeing-it-all-through, how it had all buffered against invasion.

None of that mattered.

The second ship brought about retribution

and the last look of hypocritical surprise.

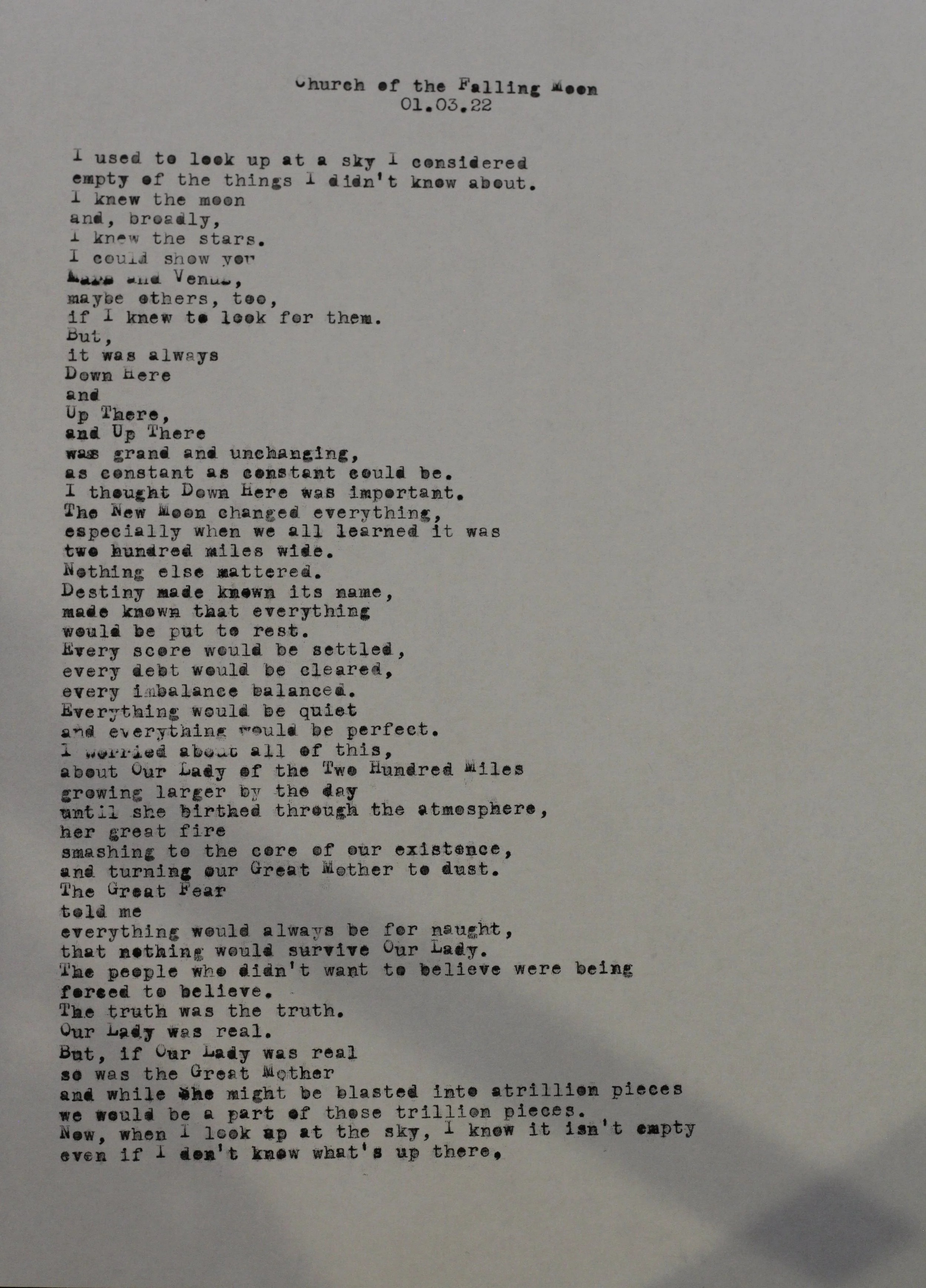

Church of the Falling Moon

Everything would be quiet

and everything would be perfect.

I used to look up at a sky I considered

empty of the things I didn’t know about.

I knew the moon

and, broadly,

I knew the stars.

I could show you

Mars and Venus,

maybe others, too,

if I knew to look for them.

But,

it was always

Down Here

and

Up There

and Up There

was grand and unchanging,

as constant as constant could be.

I thought Down Here was important.

The New Moon changed everything,

especially when we all learned it was two

hundred miles wide.

Nothing else mattered.

Destiny made known its name,

made known that everything

would be put to rest.

Every score would be settled,

every debt would be cleared,

every imbalance balanced.

Everything would be quiet

and everything would be perfect.

I worried about all of this,

about Our Lady of the Two Hundred Miles

growing larger by the day

until she birthed through the atmosphere,

her great fire

smashing to the core of our existence,

and turning our Great Mother to dust.

The Great Fear

told me

everything would always be for naught,

that nothing would survive Our Lady.

The people who didn’t want to believe were being

forced to believe.

The truth was the truth.

Our Lady was real.

But, if Our Lady was real,

so was the Great Mother

and while She might be blasted into a trillion pieces

we would be a part of those trillion pieces.

Now, when I look up at the sky, I know it isn’t empty

even if I don’t know what’s up there.

Second surgery

My heart is strong.

There are so many

people who have been taken away

in the middle of the night and

operated upon

high up in the sky.

So many of us

have felt themselves

opened up,

woken up to see

figures staring down at us,

eyeballing their work,

chattering amongst themselves,

discussing us like we are test subjects

animals soon to be vivisected:

cut open,

cut apart,

pieced back together,

closed back up,

and sent back down from the mothership

with who-knows-what removed,

and who-knows-what put inside.

No one knows where the scar on my chest came from.

My heart is strong.

My lungs are good,

and, yet, my chest has clearly been sawed open.

It feels like something is missing,

but I don’t know what isn’t there.

I know there had to be a time when I was whole,

when there was more to me

than there is now.

There has to be.

When people talk about abduction and forced surgery,

maybe they think about taking an arm off and a leg off

and reattaching them at opposite points,

or taking a hand off so it can be studied before reattaching.

I’ve always heard how complicated the hand is.

Maybe Saturday Night Wrist isn’t just about compressing the ulnar nerve,

maybe it is the arm coming off and the arm going back on.

Stranger things in this world.

Maybe something was taken out of my chest,

an unknown part of me excised like a tumour.

Maybe a memory or an emotion or a hint of spirit was taken away.

Or maybe I was just opened up

so the surgeons could see

what is inside me

and closed me back up

when they didn’t find what they wanted.

I don’t know which of those things might be worse.

A lifetime of questions

and only one sad answer.

The only reason is

the reason didn’t apply to me.

That night of terror was just one of those things,

and one of those things in a universe of things is

the smallest thing one could be.

New Moon

Maybe blood on the ground would change the heavens.

No one knew

what to make of the New Moon

when it first appeared,

and

maybe no one wanted to know what to make of it.

We already knew about new moons.

We saw the same new moon every month,

sometimes twice a month

depending on how the phases moved alongside our calendar.

No one wanted to believe it,

but willful disbelief

could only last for so long with

the new body,

night and day up in the sky,

fully formed and never phasing,

never waxing,

never waning,

as silent as the sun was loud,

as cold as the sun was hot.

When asked about the New Moon,

experts

were,

all of a sudden,

no longer experts,

and the words on expensive pieces of paper

meant little in the moment.

They tried to calm the panicked,

to still the bewildered,

tried to preach a gospel full of tropes and unknowns:

yes, the New Moon would bring many changes,

and those changes could upend everything

we knew;

but, the New Moon was neither good nor bad,

and its appearance neither fortunate nor unfortunate.

Some believed too little,

some believed too much.

The New Moon did upend everything

we knew about the world,

with there being two open eyes in the sky,

and a third that came about as regularly as it did before.

Many didn’t appreciate the change in the world,

and thinking if only the New Moon could be destroyed

or moved

or blocked somehow,

then maybe the Old Days

and the Old Ways

with only one eye fully open might come again.

Maybe blood on the ground would change the heavens.

It didn’t, of course, but

maybe

just the same.

While the first year of the New Moon

brought great hardship and great pain,

the New Moon reset the world,

balanced the world,

brought two eyes to the world.

Moonbase

A year is just a year.

It isn’t even that long.

I survived three years of plague.

My first night

alone

on the moon was a long one.

A cold one.

Maybe the longest and coldest night I’ve ever known.

Whenever I reported back to

homebase,

someone would ask if the dark had

gotten to me yet

and I always replied, no.

The darkness wasn’t what

felt

most isolating.

It was the cold,

the loneliness.

The difficulty in getting through

that first night,

the longest night,

and the long nights that came afterwards

lay in knowing the length of time

never changed.

The only thing that changed was

how I counted

time,

how I measured

all the moments

while watching our pale blue dot

from my little station,

watching the monitors for signs

of invasion,

doing it all by myself for a year.

When I signed up for the job

I thought,

what’s a year to me?

A year is just a year.

It isn’t even that long.

I survived three years of plague.

I can survive a year alone on the moon.

I can survive a year of weight on my back,

a year waiting for what we are watching to signal

they are watching back.

I can survive a year of knowing my message

will arrive too late,

no matter how early I send it.

I can survive a year

of feigning hope,

of whispering sweet nothings—

all is well, no news, everything is in order—

so someone can tell someone else

everything

is under control.

I don’t think that first night alone

I really understood

what time on the moon would be like.

I didn’t understand

how a moment

can be a moment

can be a moment

can be a moment,

but a moment isn’t always a moment

and sometimes a single moment

has the same mass as a lifetime of moments.

Sitting alone that first night on the moon

with nothing

but silence and my own arms to keep me company,

I sat through one long moment.

Maybe I thought the plague years would have helped me with time,

with knowing things happen for as long as they happen,

and that nothing is forever.

Not even forever is forever.

But on the coldest and longest night of my life

I forgot what I knew,

and for the rest of the year I remembered what I forgot

and the weight of remembering the forgotten is

heavier

than anything else

I can think of.

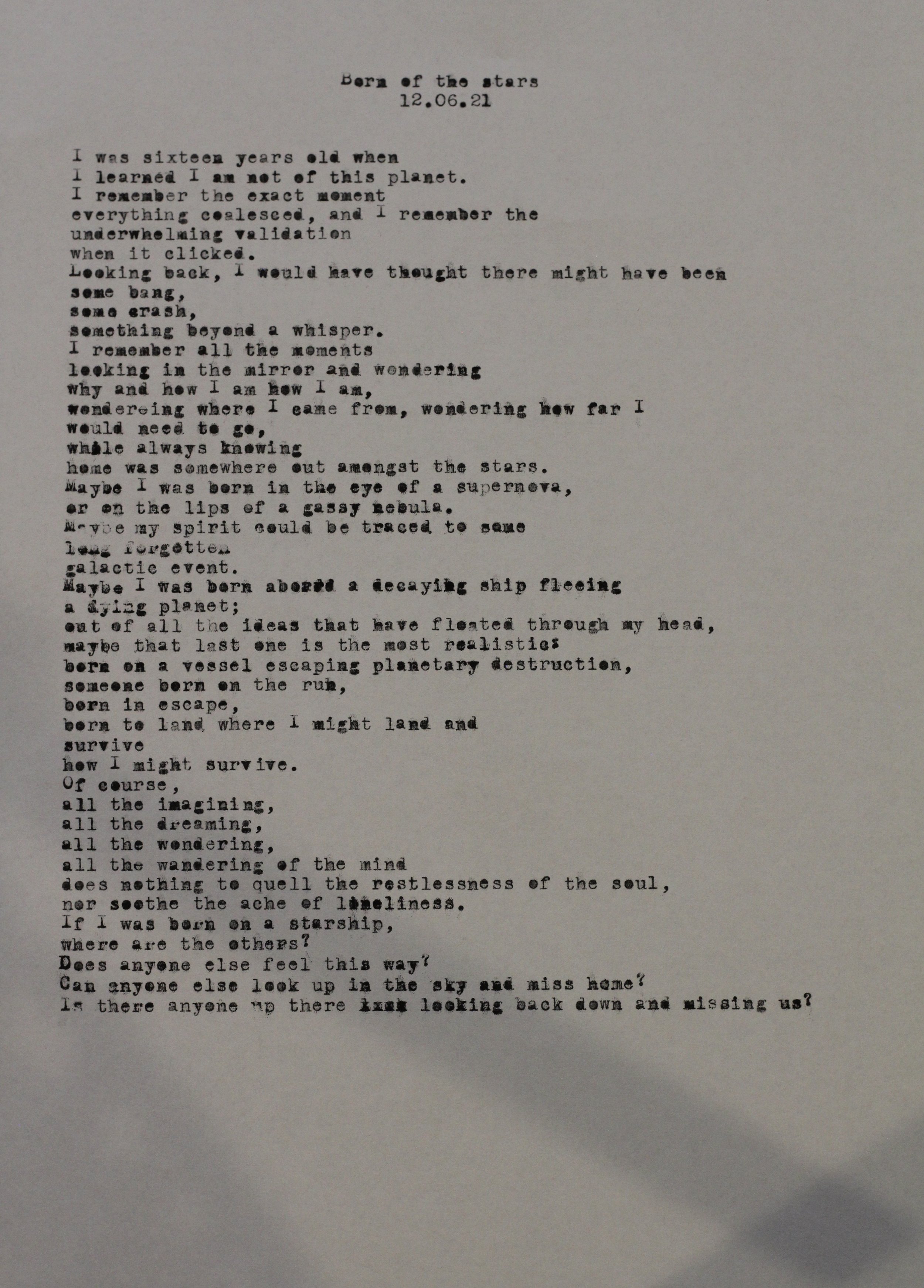

Born of the stars

Maybe I was born in the eye of a supernova

I was sixteen years old when

I learned I am not of this planet.

I remember the exact moment

everything coalesced, and I remember the

underwhelming validation

when it clicked.

Looking back, I would have thought there might have been

some bang,

some crash,

something beyond a whisper.

I remember all the moments

looking in the mirror and wondering

why and how I am how I am,

wondering where I came from, wondering how far I would need to go,

while always knowing

home was somewhere out amongst the stars.

Maybe I was born in the eye of a supernova,

or on the lips of a gassy nebula.

Maybe my spirit could be traced to some

long forgotten

galactic event.

Maybe I was born aboard a decaying ship fleeing

a dying planet;

out of all the ideas that have floated through my head,

maybe that last one is the most realistic:

born on a vessel escaping planetary destruction,

someone born on the run,

born in escape,

born to land where I might land and

survive

how I might survive.

Of course,

all the imagining,

all the dreaming,

all the wondering,

all the wandering of the mind

does nothing to quell the restlessness of the soul,

nor soothe the ache of loneliness.

If I was born on a starship,

where are the others?

Does anyone else feel this way?

Can anyone else look up in the sky and miss home?

Is there anyone up there looking back down and missing us?

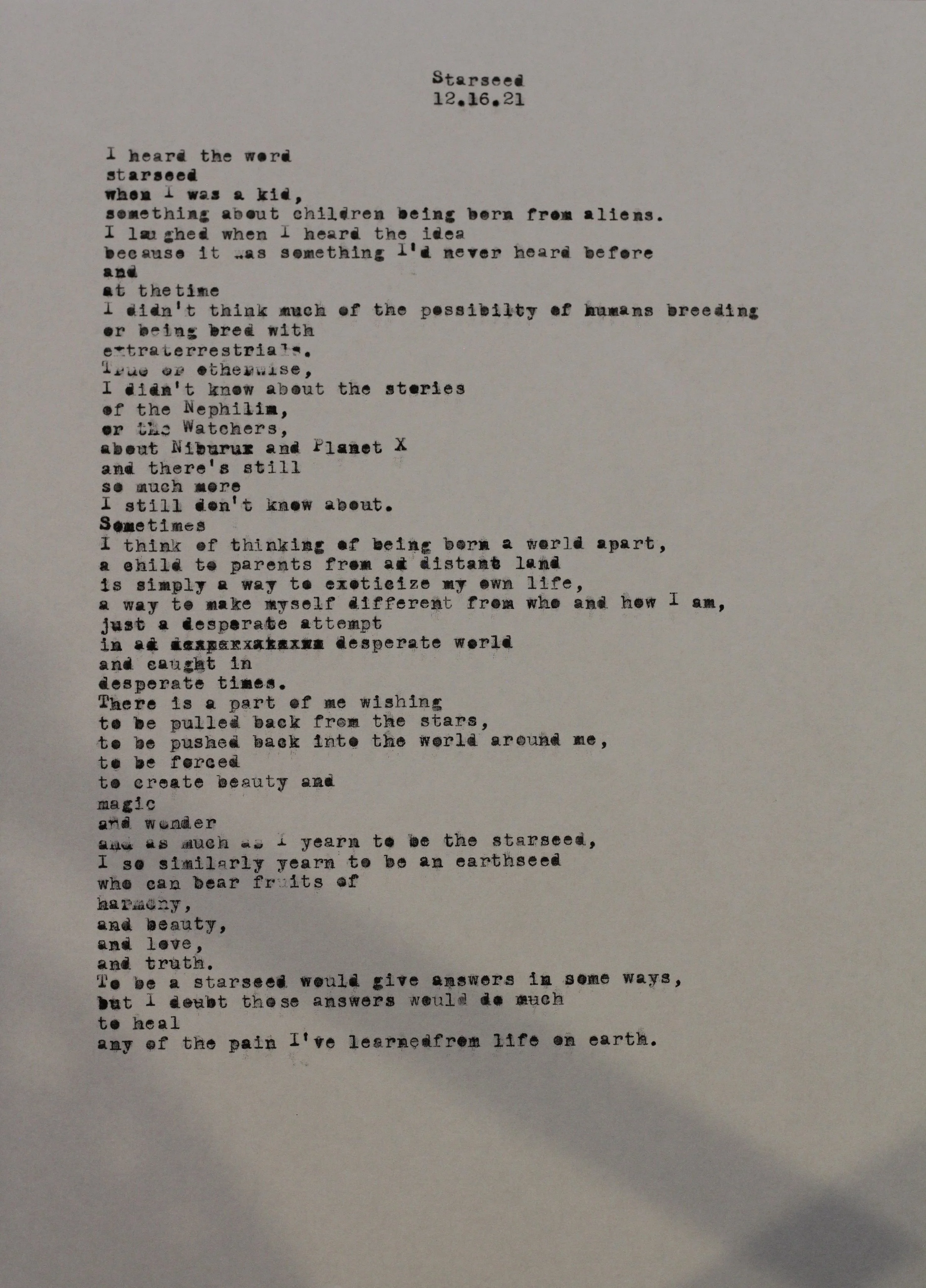

Starseed

just a desperate attempt

in a desperate world

and caught in

desperate times.

I heard the word

starseed

when I was a kid,

something about children being born from aliens.

I laughed when I heard the idea

because it was something I’d never heard before

and

at the time

I didn’t think much of the possibility of humans breeding

or being bred with

extraterrestrials.

True or otherwise,

I didn’t know about the stories

of the Nephilim,

or the Watchers,

about Niburu and Planet X

and there’s so much more I still don’t know much about.

Sometimes

I think of thinking of being born a world apart,

a child to parents from a distant land

is simply a way to exoticize my own life,

a way to make myself different from who and how I am,

just a desperate attempt

in a desperate world

and caught in

desperate times.

There is a part of me wishing

to be pulled back from the stars,

to be pushed back to the world around me,

to be forced

to create beauty and

magic

and wonder

and as much as I yearn to be the starseed,

I so similarly yearn to be an earthseed

who can bear

the fruits of

harmony

and beauty

and love

and truth.

To be a starseed would give answers in some ways,

but I doubt those answers would do much

to heal

any of the pain I’ve learned from life on earth.

Dark side of the moon

pyramids, ziggurats,

blood sacrifice and invasion

I have heard legends

about the dark side

of the moon and

wondered about that which

exists

in the shadows.

Most shadows can be expelled with light—

light of the sun,

light of a flame,

light of our hearts.

But that other side of the moon

we haven’t ever seen

except

for cryptic photos from a thousand thousand miles away,

what lurks there?

What lurks beyond the pale?

What lurks were we cannot go,

where we cannot see?

What lurks in the shadows we cannot melt away?

I know not all that reside in darkness

can be malevolent,

and I know what I cannot see might be

benevolent.

I cannot help but bear witness

to both fear of good and fear of bad,

fear of joy and fear of pain,

fear of the known and unknown alike.

More than anything else, the

fear of fear

itself sits deep in my guts.

The things I have heard about the dark side of the moon—

pyramids, ziggurats,

blood sacrifice and invasion,

plague, pestilence

and existential threat—

might be nothing more than nothing itself.

Yet,

when I stare up at the sky tonight,

tomorrow night,

every night moving forward,

I know what lies on the other side

will haunt me.

Even if there comes a day when we can see that dark side,

old fears and old worries

will still rumble in my guts.